The student accommodation sector across Europe is under pressure. Europe faces a shortage of 3.2 million student beds by 2030 (JLL, 2024, European Student Housing Report 2024). Europe's student population is expected to grow by 10% in the next five years, reaching 23.5 million, with half being international students (Real I.S., 2024, European Student Housing Market Analysis). Some 40% of European unmet demand (1.2 million beds) is concentrated in the top 40 student cities (JLL, 2023, European PBSA: Investing in the Future)

The conversation around student housing tends to focus on these supply numbers. But the European Student Living Monitor (2023-25), drawing on nearly 20,000 responses across Europe, reveals something more fundamental: where students live directly determines their capacity to succeed.

The SLM uses the Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5), a validated 0–100 mental-health scale in which score of 60 marks the threshold for good wellbeing. Students in PBSA average an MHI-5 of 58.4, just under the wellbeing threshold but higher than students living in other accommodation such as shared flats, private rentals, or student rooms (56.2), as well as those living at home with parents or relatives (51.1). The lowest scores appear among students who stay outside PBSA because they cannot secure or afford alternatives, dropping to 44.3 when no suitable housing was available, and to 42.6 when affordability was the barrier.

Across three years of data, the SLM shows that the overall average is driven down by the experiences of vulnerable groups. Students with disabilities report an average MHI-5 of 46.1, gender-nonconforming students 45.4, and those under constant financial stress (48.05) all report substantially lower MHI-5 scores. These findings help explain why the European average remains below the wellbeing threshold of 60.

What students struggle with – and what buildings can actually change

SLM asked students about 18 stressors across three domains, Academic, Social, and University Life. For each stressor, students answer yes or no to indicate whether each one affects them personally. This allows us to assess not just the prevalence of each stressor, but the extent to which being affected by it corresponds to differences in mental-health outcomes.

The largest wellbeing gaps are found in the Social category. Among the seven social stressors in the SLM, those linked to connection and belonging show the largest impact on wellbeing. Students who experience homesickness (30%) average an MHI-5 of 54.48, compared with 59.66 among those who do not, nearly reaching the wellbeing threshold. The effect is stronger for challenges connected to belonging. Students who struggle to meet people or make friends (28.2% ) score 51.71, whereas those who are not affected report 60.61. Difficulties getting on with the people they live with (16.17%) reflect the same pattern: 51.36 compared with 59.40 among unaffected respondents.

Among all stressors, loneliness has the most substantial effect. It affects 41% of respondents and produces a 13.8-point gap, the largest in the entire survey. Students who report feeling lonely score 49.89 versus 63.69 for those who don't. Students who selected "none of the above" for all stressors averaged 68.21, the highest score in the table. These results show that the challenges students report is not isolated or internal. They are relational, and whether they intensify or remain manageable depends heavily on the conditions of daily life. When students have supportive relationships, a sense of connection, and routines that work, their MHI-5 scores are higher; when they feel isolated, unsettled, or overwhelmed, the scores decline. The SLM data makes clear that wellbeing is closely tied to the environments students live in and what those environments make possible.

That's the thinking behind how operators like THE FIZZ approach design:

Student wellbeing is central to academic success, and at THE FIZZ, an SLM participant, we design every detail of student life to support it. Our all-in living concept combines private, fully furnished apartments with carefully curated shared spaces so residents can both retreat and connect; this balance is the foundation for mental stability and focused study, and why more than 90% of our tenants express positive wellbeing in our assets.

THE FIZZ claims that mental wellbeing is supported through quiet study rooms, flexible apartment layouts and regular community programming that reduces isolation and builds routine, small structural supports that make a big difference to mood and concentration. Social wellbeing and community are intentional: community kitchens, clubhouses, rooftop terraces and events create low-friction opportunities for friendships, peer learning and mutual support, all proven boosters of student resilience and performance.

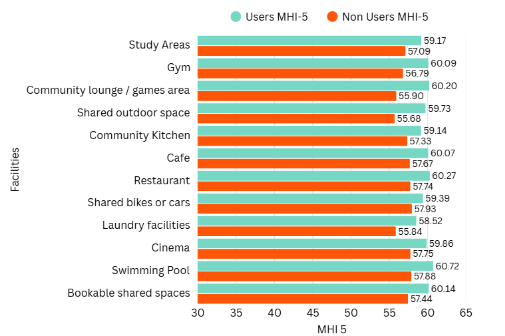

SLM data on facilities and services shows how this philosophy plays out in practice. Wherever students have access to common spaces, mental-health scores are consistently higher and shape how students cope with the everyday pressures of living away from home. Students who use communal spaces report an MHI-5 of 60.20, compared with 55.90 for those who never do. Shared outdoor areas follow the same pattern (59.73 vs 55.68), as do gyms (60.09 vs 56.79). Buildings that offer a mix of quiet spaces, social spaces, and outdoor/active spaces give students the ability to shape their own day by choosing the environment that matches what they need.

Figure 1: MHI-5 Scores by Facility Use

What activates those spaces i.e. the programming and people that turn them from empty rooms into living infrastructure, matters just as much. The strongest effect comes from regular participation: the 2025 SLM data shows that students who take part in organised events score higher than those who never join (60.29 vs 56.52), and student-led groups show a similar shift (60.41 vs 57.53)- almost a 4 point difference that places frequent participants well into the good mental health range. Even the presence of an on-site community manager creates a small but consistent difference in how supported students feel (59.40 vs 57.29). It creates a sense that someone is paying attention, that the place is cared for, and that you're not left to navigate everything alone.

What makes this work isn't any single amenity but how they function together as a system. A student struggling to meet people benefits from the community kitchen, but also from the gym where they see the same faces, the outdoor terrace where informal conversations happen, the organized events that lower the stakes of socializing. The architecture may not change, but the experience of living in it does. These spaces aren't secondary additions, the building becomes a setting that helps students steady themselves, a place that reduces strain and pressure for the students instead of becoming another source of it.

Why Safety and Stability Matter for Student Wellbeing

Safety and comfort provide the reliable baseline every student needs to thrive. THE FIZZ properties use secure building management, video surveillance in public areas and dedicated security services so students can feel safe coming and going. In a period of significant life change, a new or first home away from home can be a source of additional stress; comfortable, all-inclusive apartments — with predictable costs and services — reduce this stress so time and energy go toward study and wellbeing.

Safety and reliability are key aspects that THE FIZZ addresses: secure buildings, on-site staff, and apartments where the essentials are taken care of. As SLM Data shows fewer than a third of students (29.7%) say they have access to security staff. Just over half (51.7%) have regular cleaning of shared spaces, and around two-thirds (63.5%) have reliable repairs or building management. These gaps directly shape how students feel at home. The intention behind THE FIZZ’s approach sits exactly in response to this: when basic safety and upkeep are a given rather than a question mark, students don’t spend energy worrying about their environment. They can focus on study, routine, and settling in, because the building is doing its part instead of adding to the pressure.

Beyond four walls:

These practices reflect the wider mission of THE FIZZ: housing that is more than four walls, combining quality apartments, services, and a vibrant community to help students flourish academically and personally. By treating wellbeing as an operational priority — not an add-on — THE FIZZ supports tenants’ ability to perform optimally in life and learning.

The SLM findings reinforce this approach. Across three years of data, the SLM identifies three pillars that shape student wellbeing: affordability and availability, community, and targeted support. Viewed alongside THE FIZZ’s approach, these insights show that wellbeing improves when some or all of these elements are intentionally built into housing environments. Students in supportive, well-connected settings report higher happiness scores, stronger belonging, and a greater likelihood of recommending their institution. Together, these patterns show how the wider accommodation ecosystem contributes to students’ ability to succeed.

END

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

*The MHI-5 serves as a globally recognised and extensively documented measure of well-being. It operates on a scale from 0 to 100, where scores above 60 indicate good mental health, reflecting optimal well-being.

The full 2023-25 overview Student Living Monitor report, offering detailed insights into these findings, is available for download HERE (November 2025)

Sources:

Student Living Monitor (SLM): The Student Living Monitor is an annual survey by The Class Foundation to explore the connection between student happiness, experience and living environments in Europe. Engaging thousands of participants across Europe, the survey offers valuable insights into students' experiences and provides recommendations for the sector. The 2023-25 overview report is available HERE.